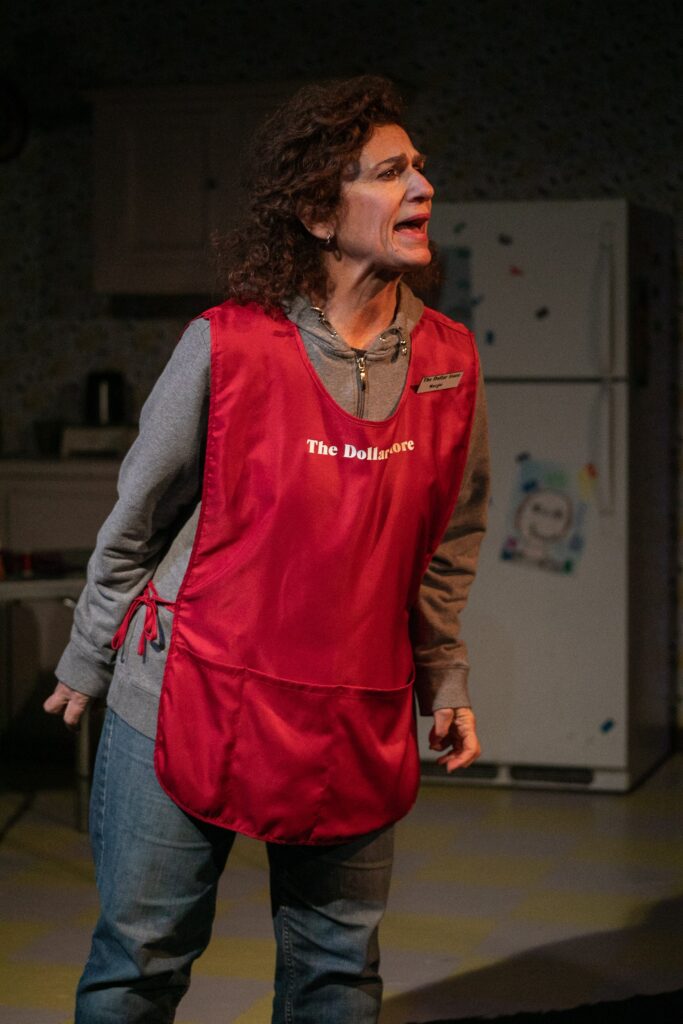

When Margie Walsh loses her job at a South Boston dollar store, she reaches out to old flame Mike, a Southie boy who left the neighborhood and became a successful doctor. Margie’s attempt to hit Mike up for a job takes on a threatening cast when she realizes the power a secret from Mike’s past holds. From Pulitzer Prize-winner David Lindsay-Abaire, GOOD PEOPLE looks at the dangerous consequences of choosing to hold on to the past or leaving it behind.

When Margie Walsh loses her job at a South Boston dollar store, she reaches out to old flame Mike, a Southie boy who left the neighborhood and became a successful doctor. Margie’s attempt to hit Mike up for a job takes on a threatening cast when she realizes the power a secret from Mike’s past holds. From Pulitzer Prize-winner David Lindsay-Abaire, GOOD PEOPLE looks at the dangerous consequences of choosing to hold on to the past or leaving it behind.

Since class identity and class conflict are so important to the dynamics of Good People, it’s crucial that the physical settings of the action convey the social standing of the people who inhabit them. The play contains six scenes, four of them set in South Boston: one in an alley behind a Dollar Store; one in the apartment of the main character, Margaret (Margie) Walsh; and two in a church basement where Margie and her friends play bingo. The remaining two scenes take place in the Boston area, but at a vast social distance from Southie. One is set in the downtown medical office of a physician who was born in South Boston, but who has moved on to an affluent upper-middle-class life. The other takes place in a home in Chestnut Hill, a suburb a few miles west of Boston proper, originally developed by Frederic Law Olmstead, the designer of New York’s Central Park. Currently the average price for a single-family house in Chestnut Hill is more than two million dollars.

We first encounter Margaret in an alley behind the down-market store where she works. “There’s a dumpster back there, a rusty chair, and a door labeled ‘Dollar Store—Deliveries Only.’” This space doesn’t belong to Margaret—instead it’s an impersonal, functional area reflecting nobody’s “taste.” And Margaret has been taken there to be fired.

We next see her in the kitchen of her apartment in Southie, a room that’s, “small and run-down.” The script mentions no personal touches that Margaret might have applied to this room, no flourishes of “taste.” And the space doesn’t really belong to her. Much of the conversation in the scene focuses on whether she’ll be able to pay her rent now that she has lost her job. In the absence of the rent money, Margie is there provisionally, only as long as her landlady allows. She’s a transient in her own home.

MARGARET

Her life has been haunted by a fateful decision made in the past that comes to light in the course of the action. She has built the narrative of her life around a decision she made during the summer after her junior year in high school. It was then that she chose not to prevent Mike from going off to college. Instead of telling him that she was pregnant with his baby—because, as she insists, she was nice—she let him leave Southie to pursue a future that would see him become a prosperous Boston physician and a suburban squire in Chestnut Hill.

MIKE

He also goes through a similarly upsetting process as he is forced to confront truths about himself that he would rather keep hidden behind a curtain of sentimental Southie memories. We probably all have people in our pasts whom we would rather not meet again, especially old flames. It can be painful or embarrassing to see what time has done to that formerly young and beautiful girl; or to have her see what time has done to us. But Mike has aged well and has put together an enviable life. So what is he hiding from?

KATE

Her background is starkly different from Mike’s Southie past. The daughter of a prominent physician, she was raised in Georgetown, a swanky neighborhood in Washington, D.C. An upper class black girl, she was secure enough in her social and economic circumstances to dabble in bohemianism during her college years. She attended graduate school, presumably earned a Ph.D. in English, and is now teaching literature at Boston University.

STEVIE

A young man who grew up in Southie. He has neither fled the old neighborhood nor become disappointed and embittered by his life there. Instead he might be seen as the face of a new Southie by being free of the old social and ethnic prejudices.

JEAN

Is irked by Margie’s misfortunes, angry at Dottie for showing up late to babysit, skeptical about Margie’s claim that Mike is “good people,” determined to harass Stevie for firing her friend. She’s a cynic and a schemer.

DOTTIE

She seems to exist in a continuous fog of mild confusion. She has trouble keeping Mikey Dillon and Kevin Dillon straight in her head, and she can’t grasp the fact that the girl Stevie is dating doesn’t work at the Chinese restaurant but at the Dollar Store. The one activity that keeps her focused is making and selling her toy rabbits, objects some people actually buy, which means that Dottie is in fact in touch with something real.

Two of the six scenes of Good People take place during bingo games. Margie and her friends fail to win. What is this telling us? Pretty clearly, we are being reminded of the role of chance—of pure luck— in the outcomes of life. Margie is convinced that her life has been a succession of misfortunes brought about by fate, not produced by her own choices.

On the other hand, Mike, whose life has been marked by professional and economic success, wants to believe that things happen because people make them happen, that he escaped from Southie thanks to his own hard work and individual initiative. He is proof that being born in South Boston or anywhere doesn’t have to determine the course of the rest of your life.

So what does account for the outcomes of life: luck or choice? The fact that we last see Margie losing at Bingo suggests the former. On the other hand, she is still choosing not to hold Mike responsible for Joyce. So the play leaves us balanced on the edge between life as a lottery and life as an experience designed by those who live it.

Archival Photos by Marlee Melinda Andrews