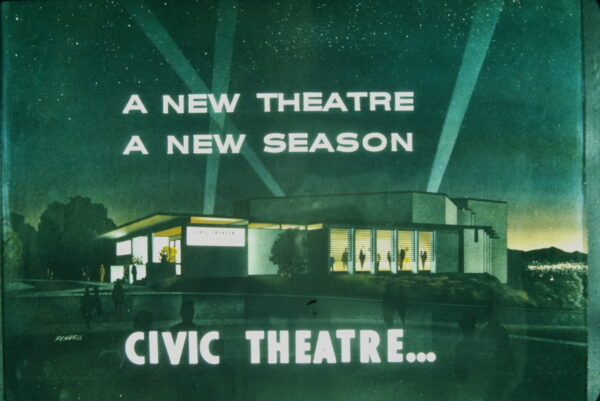

Advertisement for the new building and season in 1967

By Jim Kershner

August 2022

In November 1946, a tiny notice appeared in the Spokane Chronicle announcing the formation of a new dramatic organization, Spokane Civic Theatre.

At this point in Spokane’s history, the city had already witnessed a parade of drama clubs, theater groups, repertory companies and “little theaters.” Every one of them had come and gone. Live local theater had been silent since 1942. A group of local theater educators, theater artists, and theater lovers wanted to end that drought. They knew it would not be easy, as evidenced by the following confession: “Right now, the new Civic Theatre has a housing problem.” In other words, the Civic Theatre had no theater.

The steering committee, led by local legend Dorothy Darby Smith, was unfazed. They forged ahead with plans to produce an adaptation of Tom Sawyer, in conjunction with another fledgling organization, the Spokane Children’s Theatre. Rehearsals began in schoolrooms, living rooms and a cramped radio studio. The downtown Orpheum Theatre finally agreed to rent its space to the Civic — but only when it wasn’t showing films. For that reason, the Spokane Civic Theatre’s inaugural performance took place at a most unusual time: 10 a.m. on a Saturday morning, February 15, 1947.

Smooth was not the word to describe this particular debut. The group had to build all of its sets in an organizer’s basement. They had to truck the sets to the Orpheum on Friday night and wait until the last movie ended. Then they had to frantically assemble the sets until 3:30 a.m. The Chronicle noted that, “The Civic Theatre group, including Grace Gorton, director, were a tired lot.” During the performance itself, Bosco, the Orpheum’s house cat, strolled onto the stage, peeked around one of the set pieces, and “made a rapid but dignified exit amid thunderous applause.”

How did this bedraggled group evolve into one of Spokane’s premier cultural institutions? To steal a line from Shakespeare, thereby hangs a tale.

In some ways, Spokane Civic Theatre was a smash hit from the beginning. Tom Sawyer ended up playing to more than 14,000 schoolchildren and even going on the road to Lewiston. Encouraged, organizers incorporated as Spokane Civic Theatre, Inc., in September 1947, and announced a three-play season with more mature and meaty fare. On October 1, 1947, it opened the Pulitzer-winning political comedy-drama The State of the Union at the Post Theater, another downtown movie palace. The critic for The Spokesman-Review said the show’s quality and the hefty attendance “should establish the theater as a valued cultural asset for the city.” Civic followed with a production of Noel Coward’s Blithe Spirit at the Post.

Audiences were gratifyingly large. Spokane Civic Theatre was well on its way. Becoming a longstanding civic institution, however, required sustained commitment from volunteers, theater artists, and community donors. The strongest evidence that the Spokane Civic Theatre was here to stay came in 1957, when it took over an old movie theater on Riverside Avenue. Volunteers scraped, painted, hammered, and transformed the old theater into the Civic’s own performing space, which they called Riverside Playhouse. The Spokesman-Review’s critic said the move had finally brought “live theater to downtown Spokane on a scale the city deserves.”

Civic was not satisfied. By 1965, it had dreamed up an even more audacious plan: Building its own state-of-the-art theater. This was something exceedingly rare for a community theater, yet it would solve that “housing problem” once and for all. The Board purchased land next to the old Spokane Coliseum and within a year, had raised enough money to proceed. Within two years, it was finished. The first performance at the new Spokane Civic Theatre was the musical, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, on October 6, 1967.

A second, smaller, performing space called the Studio Theatre was added as part of an expansion in 1972. This small “black box” theater was later renamed the Firth J Chew Studio Theatre, in honor of a crucial guiding hand and volunteer. Today, Civic has the distinction of owning its own land and its own building, setting it apart from many of its peers.

Civic was also undergoing another kind of expansion — an artistic expansion. With two performing spaces, it could stage big crowd-pleasing musicals and hit plays upstairs, but it could also produce more edgy, experimental and occasionally controversial work downstairs in the intimate Firth J Chew Studio Theatre. Examples included Angry Housewives, Falsettos, Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, Wit, and Metamorphoses, which featured a full swimming pool for a set.

The Studio Theatre also hosted another ambitious endeavor: a new play competition, called the Playwrights’ Forum Festival, featuring new works from around the region. This was another indication that Civic was an outlier among community theaters. Another was the sheer quality of the talent pool and the productions. This was obvious to many theatergoers, including myself, who arrived in Spokane in 1989 as The Spokesman-Review’s theater critic. Over the next two decades, many of the best shows I saw were not the professional touring shows, but Civic’s. The knowledge that this was a community theater, in which all of the actors and many members of the production team were volunteers, made this even more impressive.

Artistic quality is hard to quantify. There is, however, one widely accepted measure of artistic quality in the community theater world, and that is the American Association of Community Theatre’s National Festival, in which regional winners compete against each other before a team of judges. Civic routinely won the Northwest regional competitions, and then, in 1989, Civic’s Getting Out won first place in the nation. It was subsequently invited to be the U.S representative to the World Amateur Theater Festival in Monaco.

This was just the beginning of a remarkable run at the AACT’s National Festival. Over the next decade, Civic finished in the top two in the nation for Mama Drama and Assassins, and won the top prize again for Lonely Planet. Civic has continued to win numerous national and regional awards ever since.

Back in 1947, that long-ago theater critic predicted that Spokane Civic Theatre would someday become “a valued cultural asset for the city.” Not everyone believes theater critics know what they are talking about. Yet that one turned out to be 100 percent correct.